Here we outline the basic intention of the college, as one of **infrastructuring** radical practice with **tools for conviviality** (Ivan Illich’s notion), thus constituting **vernacular capability** in knowing, communicating and organising in mundane work- and life-settings, for the common weal.

We bring together two perspectives emerging in the 70s and the 90s - tools for conviviality and infrastructuring - and add in a third ('the generative dance of knowing') which brings a basic framing to the work of 'formacion' in the college.

**70s - Tools for conviviality** In the 70s, Ivan Illich developed a thoroughgoing critique of ‘industrial’ forms of provision - of cultural practices such as education, practices of material wellbeing such as healthcare, and material provisions such as housing and transport.

Many of these services and resources were made through centrally-specified provision in the state sector - as with compulsory primary and secondary education, and often with healthcare - but Illich’s main target was **the professionalised mode** in which provisions have been increasingly made, both in the market and the state.

He argued, in opposition to this, for regimes of practice in which **vernacular understanding and capability** could be mobilised by communities and individuals, to organise life locally in ways determined locally and peer-to-peer and in local context, in a completely sifted balance with centralist or elite intervention, specification and regulation.

Illich argued for deschooling, in which recognised and valued places and means of learning would be distributed throughout the lifeworld, and for **tools for conviviality**, by which he meant far more than material items. He also - perhaps mainly - had his eye on economic and cultural **institutions** which would facilitate convivial living as distinct from reproducing their own hegemony and the powerlessness of ‘ordinary people’, which is what he saw occurring in professionalised and often mandatory ’industrial’ provision.

I feel this intention is so important that I have named the venture of formacion proposed here as **‘a college of conviviality’**. Illich’s expanded sense of ‘tools’ is central, and the college is centrally concerned with developing the capability for making of tools across the whole range from material artefacts and digital means, to cultural, economic and aesthetic formations. See also Tools for conviviality

**90s - Infrastructuring and capability in the design of design** In the 90s, attention began to focus on the provision of infrastructure, and ‘infrastructuring’ as a mode of practice began to receive analytical attention.

This specifically occurred in relation to entire emerging technologies, notably the digital technologies that were initially and charmingly called ‘the new technology’ or ‘microtechnology’ (meaning microprocessors).

This expanded to infrastructures of (digital) **media**, (digital) **communication** and - underlying these - infrastructures of **formal rules, algorithms, classifications and forms of executable code and code-driven machinery**, through which chains of material actions in the world could be programmed, thus materially moving, mobilising, allocating or giving access to resources, without direct human evaluation or even recognition. This is machine-based **fiat** on a very large, systematic, scale.

Clearly this is an aspect of the turn from the Fordist (centralist, massified) mode of capitalism to the post-Fordist mode.

At the same time, as the movement became apparent there was a counter-movement around **skill**. This often was expressed as a conservative resistance to ‘deskilling’ (which was a well established Fordist tendency, ramping up with post-Fordism). But sometimes the changing situation was also engaged with as a search for acceptable and desirable forms of **‘reskilling’** and recomposition of Labour - for example, equalising the opportunity and power of women, of ethnic minorities and - embracing Illich’s vision - of ‘ordinary working people’ in their everyday lives, in relation to both professional and ‘public’ (state) formations.

These complex and sometimes contradictory movements were present in the 90s, for example, in emergent fields of **design and development**: 'human centred' design, computer supported cooperative work, participatory design of IT-based workplace tool infrastructures, and the ‘interaction design’ variant of human-computer interaction.

>See also: Participatory design To be added xxx

In a broad way - more in some countries’ cultures than in others - practice in these fields drew on the earlier movements: for workers’ control, workers’ self-management, bottom-up planning and design, rank-&-file power and capability, workers’ plans and workers’ inquiries, ‘community’ development, ‘voices from below’ and ‘unheard’ voices; and so on.

It seems important to bring together . . - this now-present awareness of **infrastructuring** as a manifestly-occurring kind of (capitalist. statist, extractivist, supremacist etc) process that can and should be done in other ways, with . . - the earlier awareness (arising with Fordism, much aggravated and deepened in post-Fordism) of the powers systematically acquired by **professionalised, mandatory and almost inescapable** ‘industrial’ provision, and . . - the historical possibility that such provision can be made and mobilised - and crucially, **designed** - in vernacular ways, in what Gramsci first referred to (in a Fordist context) as an **‘organic intellectual’** mode.

This has received a further major boost with the emergence and then prevalence of **peer-to-peer (P2P) production** and the agile mode of software production (and digitally-mediated supply chain operations) in the heart of post-Fordism.

**The generative dance of knowing** These two historical movements of perception and capability are joined, in this present proposal, by a third frame which helps in addressing the richer, expanded sense of ‘tool’ that comes with the conviviality frame.

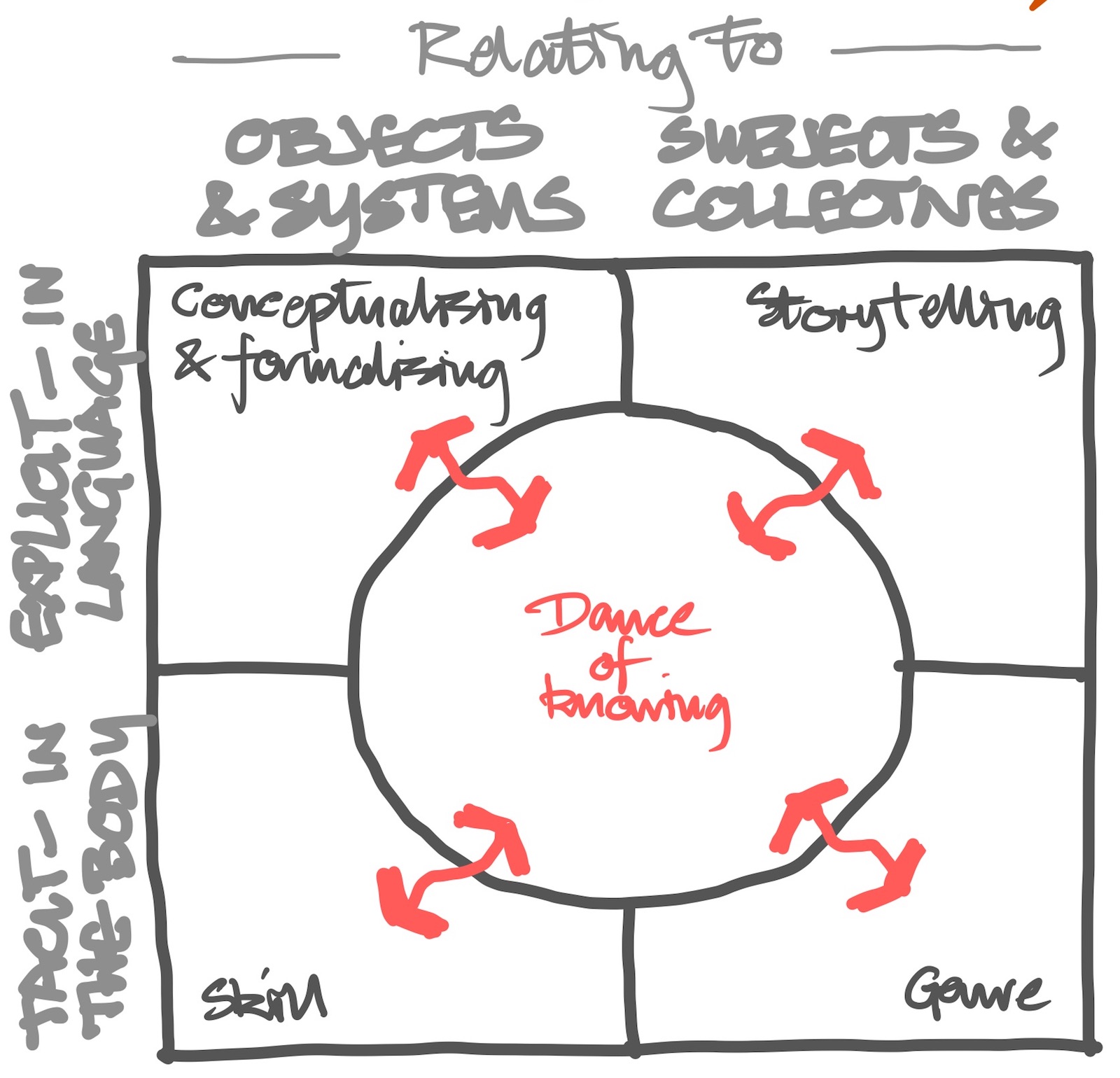

Post-Fordist attention moved towards ‘knowledge’ and the systematic producing, mobilising, holding and circulating of knowledges and capabilities, for example, with ‘the knowledge economy’ and ‘knowledge intensive business services’. In the 90s - in the glory days of 'knowledge management' - a frame was developed which looks simple but - after using it for nearly 25 years - I feel enables a very rich approach to - how knowledging is in fact done (performed), **as a practice**, - how knowledges and skills relate to **tools** of different kinds (including Illich’s kinds), and - how **diverse modes of knowing and capability** coexist, hybridise and mutually inform and enable one another - and together, across diverse modes of rigour, constitute **literacy** - in the skilful conduct of practice in communities.

The frame was developed by John Seely Brown and Noam Cook of the corporate R&D lab of the Xerox corporation. They called it ‘the generative dance of knowing’.

Cook & Brown - 'The generative dance of knowing'

> S. D. Noam Cook & John Seely Brown (1999), Bridging Epistemologies: The Generative Dance Between Organizational Knowledge and Organizational Knowing, *Organization Science* , August 1999, 10, 381-400. DOI: 10.1287/orsc.10.4.381

--- >Note: Until this section is further developed: the dance of knowing is referenced as the core of landscape §2 in the foprop weave and as central in understanding formacion. See these pages . .

Here we describe the cultural landscape - Labour powers and formations of labour powers, and their radical transforming and mobilising.

Both formacion and making the living economy must skilfully interweave practical things in what I'll describe as **three landscapes** - the material, the cultural and the aesthetic.

The page above is part of the script for an animated slide presentation. The opening page of the presentation, and a link to an mp4 video of the presentation are here. The dance of knowing is easier to get a feel for from the video.